The Kangchenjunga Story A brief history of Kangchenjunga

Joe Brown’s and a British team’s epic first ascent of the third highest mountain in the Himalayas, Kangchenjunga, the challenge that Aleister Crowley, Paul Bauer and Gunther Dyhrenfurth failed to overcome.

At around two in the afternoon on Wednesday 25th May 1955, a pair of young British climbers, George Band and Joe Brown, found themselves sitting on an icy ledge at the top of a steep slope. Back home George was a geology student who had recently graduated from Cambridge, Joe a general builder who had left school at fourteen. If it hadn’t been for climbing, they might never have met but right now they were partners, the spearhead of the British Kangchenjunga Reconnaissance Expedition.

While they gobbled down toffees and swigged back luke warm lemon cordial, the wind blew flurries of snow over their heads. At around 27,800 ft they were undoubtedly the highest men in the world but they were still some 350 vertical feet short of their goal. And that was a big problem because they were way beyond their turnaround time.

If everything had gone according to plan, they would have been on their way down. Time was running out and so was their oxygen. They had just two hours left, enough to reach the summit but not enough to descend safely. If they went on, there was no guarantee of success and they risked having to sleep out in the open with nothing but the clothes they were wearing to protect them from the freezing cold.

So what should they do – stick or twist? Carry on up or retreat to hand on the baton to their teammates in the second summit party? Over the last five decades there had been four previous expeditions to Kangchenjunga, the third highest peak in the world. Nine men had died, trying to achieve what Everest leader Sir John Hunt called the greatest feat in world mountaineering.

Were they willing to risk everything for fame and glory or was it finally time to turn back?

The Great Beast 666

What happened next is an extraordinary story in itself but it’s also the final chapter in a much longer saga which goes back to the beginning of the twentieth century. It’s a tale whose cast includes some of the most talented, most driven and occasionally most eccentric characters in the history of mountaineering: men like Aleister Crowley, the occultist nicknamed the ‘Great Beast 666’, Paul Bauer, the fanatical German climber and Nazi official, and Gunther Oscar Dyhrenfurth, the mountaineer known to his friends as GOD.

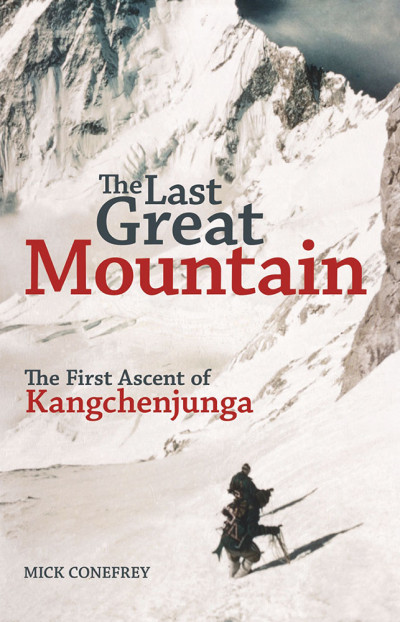

For the last three years, I’ve been researching the climbing history of Kangchenjunga for my book The Last Great Mountain, talking to survivors of the first ascent and tracking down diaries, letters and other documentary evidence. It is easy to see why so many climbers became so obsessed with ‘Kanch’. Unlike Everest and K2, it is relatively accessible and is visible from the hill towns of Northern India. Initially it was thought to be the highest mountain in the world and even when British surveyors discovered that Everest was about a thousand feet higher and K2 about eighty feet its superior, Kangchenjunga was still regarded as a great, if not the greatest challenge in Himalayan mountaineering. It’s combination of extreme altitude, climbing difficulty and appalling weather made its ascent a virtually impossible task.

The Wickedest Climber in the World

Aleister Crowley, the man dubbed ‘The Wickedest Man in the World’ by the British press, was the first to have a crack at it, leading a team of Swiss climbers. Crowley had made the first attempt on K2 a few years earlier and had famously become so ill with malaria that he started threatening to shoot his team-mates. Kangchenjunga went better but ended with an accident which killed four members of his team and prompted a very bitter and acrimonious controversy.

In the late nineteen twenties, a team of German climbers led by Paul Bauer, made two quite amazing attempts, in which they spent weeks literally trying to tunnel their way through ice-formations on the North East Ridge. They didn’t get anywhere close to the summit and only narrowly escaped with their lives, but their 100% commitment won them praise from climbers all around the world. In between Bauer’s two expeditions, an international team under Gunter Dyhrenfurth made an attempt from the other side of the mountain in Nepal. It climaxed in a huge avalanche which cost Sherpa Chettan his life and almost wiped out the whole climbing party.

Unfinished Business for 1955

When Joe Brown and George Band arrived on the mountain with an all British team in 1955, no-one was sure whether Kangchenjunga could be climbed at all. The expedition was led Charles Evans, who had come within a whisker of being the first man to summit Everest two years earlier. He was an inspirational leader who had learnt his lessons well after spending much of the previous five years in the Himalayas but he knew he had a job on.

At 24, Joe Brown was the ‘Theo Walcott’ of his team, utterly different from the usual Oxbridge educated elite who dominated British mountaineering. Some in the climbing establishment were very dubious about his inclusion, but Charles Evans was willing to take a risk and as the expedition progressed, he was more and more sure that he’d made the right choice. Joe ate more than anyone else, smoked more than anyone else and spoke with such a strong accent that the Sherpas thought he was from another country but he proved himself to be an exceptional all-round mountaineer.

Charles Evans

Charles Evans’s team overcame altitude sickness, avalanches and freak storms to get themselves into a position where Joe Brown and George Band could strike out for the summit. Right at the end of their attempt, they came up against Kangchenjunga’s equivalent of the Hillary Step on Everest, a steep wall of rock just under the summit which at just under 28,000 ft looked like an impossible climb. Fortunately, Joe Brown was up to it, using his favourite technique of ‘hand-jamming’ to work his way up a narrow crack in the rock.

When he and George Band eventually got to the top, following an agreement with the Maharajah of Sikkim, they left the final snow cone on the summit ridge untrodden. It was an amazing achievement: the last great mountain to be climbed, the first time a pair of British mountaineers had stood on top of an 8000m peak. Back home in Manchester, Joe Brown, got a typically effervescent reception from his mates at the legendary Rock and Ice club: “No man is a hero in his own house. The Rock and Ice were like brothers, how would you expect them to react? They’re British, the most you’d get was ‘well done lad’. I got no free drinks.”

Published on: Rock and Ice, June 2020.